Human beings are the most intelligent, and therefore important, of all the world´s species, right? We deserve our superior status over other animals because of the following scientific truths: that only humans are self-aware and feel empathy, that we are unique in our abilities to use language and tools, that only we can recognize ourselves in a mirror and understand the passing of time.

But advances in cognitive ethology (the scientific study of animal intelligence, emotions, behaviors, and social life) have now disproved these ´truths´, showing that many other creatures also display a complex range of emotions, highly evolved communication skills, compassion for others, and even intelligence that rivals- or surpasses- our own. These ground-breaking studies force us to ask some uncomfortable questions about our place in the world, and have caused leading experts to call for a radical rethink of the way we treat other animals.

Communicative mice, kindly rats and compassionate chickens

Among the findings are that yes, fish do feel pain , and not only that but acidic water actually makes them nervous. Chickens are not only very intelligent, they can also feel each other´s pain and demonstrate physiological signs of concern and distress at the suffering of their young.

Similar conclusions were drawn in a cruel study of mice who were doused in acid. Not only were the empathic rodents more sensitive to the pain of their peers than to their own agony, but researchers also suggested they “might be talking to each other” about their pain, too. Take a moment to let that sink in….

And while rats don´t have the best of reputations, there is much research to suggest they too are compassionate, communicative and highly intelligent. One group of scientists found that, given the choice, rats prefer to free others from a cage rather than help themselves to candy. What´s more, the rats had not been taught to open the cages in advance. Researcher Peggy Mason noted: “That was very compelling … It said to us that essentially helping their cagemate is on a par with chocolate. He can hog the entire chocolate stash if he wanted to, and he does not. We were shocked.”

Older studies from the 1950s and 60s found that both rats and rhesus monkeys will refuse to pull a food lever if it results in an electric shock for another group member. One monkey went without food for 12 days rather than hurt one of his peers. Another researcher who was attempting to free two baby mice trapped in a sink noted how the stronger rodent showed concern for his exhausted friend, even carrying food to him until he was strong enough to move.

Some of the most heart-warming tales of expressive love and empathy come from the great apes, our closest relatives. Moral philosopher Mark Rowlands recounts the following:

Chimps in the Cameroon mourn the passing of their friend Dorothy, October 2009. But why does this ´human-like´behavior surprise us? CREDIT: Monica Szczupider, Daily Mail

“Binti Jua, a gorilla residing at Brookfield Zoo in Illinois, had her 15 minutes of fame in 1996 when she came to the aid of a three-year-old boy who had climbed on to the wall of the gorilla enclosure and fallen five meters onto the concrete floor below. Binti Jua lifted the unconscious boy, gently cradled him in her arms, and growled warnings at other gorillas that tried to get close. Then, while her own infant clung to her back, she carried the boy to the zoo staff waiting at an access gate.”

He also tells the story of Kuni, a captive Bonobo chimpanzee in the UK: “One day, Kuni encountered a starling that had been stunned during some misadventure. Kuni picked up the starling with one hand, and climbed to the top of the highest tree in her enclosure, wrapping her legs around the trunk so that she had both hands free to hold the bird. She then carefully unfolded its wings and spread them wide open. She threw the bird as hard as she could towards the barrier of the enclosure. Unfortunately, it didn’t wake up, and landed on the bank of the enclosure’s moat. While her rescue attempt didn’t succeed, Kuni certainly seemed to act with good intentions, and tried to make amends by guarding the vulnerable, unconscious bird from a curious juvenile for quite some time.”

Love, empathy…and some strange animal friendships

Rowlands argues that humans absolutely do not have the monopoly on moral behavior (if we ever did). The sheer number of incredible stories to back up his claim is impossible to detail in one article, but here are some more examples, summarized by Marc Bekoff Ph.D, award-winning scientist, author and co-founder of Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals : “A teenage female elephant nursing an injured leg is knocked over by a teenage male. An older female sees this happen, chases the male away, and goes back to the younger female and touches her sore leg with her trunk. Eleven elephants rescue a group of captive antelope in KwaZula-Natal; the matriarch elephant undoes all of the latches on the gates of the enclosure with her trunk and lets the gate swing open so the antelope can escape. A male Diana monkey who learned to insert a token into a slot to obtain food helps a female who can’t get the hang of the trick, inserting the token for her and allowing her to eat the food reward. A female fruit-eating bat helps an unrelated female give birth by showing her how to hang in the proper way. A cat named Libby leads her elderly deaf and blind dog friend, Cashew, away from obstacles and to food. In a group of chimpanzees at the Arnhem Zoo in The Netherlands individuals punish other chimpanzees who are late for dinner because no one eats until they’re all present.”

Animals can have surprising bedfellows

CREDIT: xaxor.com

“Do these examples show that animals display moral behavior, that they can be compassionate, altruistic, and fair?” Asks Bekoff. “Yes, they do. Animals not only have a sense of justice, but also a sense of empathy, forgiveness, trust, reciprocity, and much more as well.” Interestingly, he adds, these “good emotions can be shared by improbable friends, including predators and prey such as a cat and a bird, a snake and a hamster, and a lioness and a baby oryx.” Other cases of strange friendships include a cheetah and a retriever, a lion and a coyote, a dog and a deer, a goat and a horse, and even a tortoise and a goose. Cats have been known to adopt and feed chicks and baby hedgehogs, while one recent case centered on a disabled dolphin who was adopted by a family of sperm whales.

It seems that compassion has no boundaries. Clearly, co-operation in the animal kingdom is not only common, it´s a crucial survival strategy which humans would be wise to learn from. Charles Darwin himself wrote: “Any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts…would inevitably acquire a moral sense of conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well-developed…as in man.”

Is this what is happening now, throughout the animal kingdom? According to experts, all birds and mammals, as well as octopuses and too many other species to list, appear to be a whole lot smarter than we ever gave them credit for. The following is an excerpt from the Cambridge Declaration of Consciousness (a prestigious, official recognition of animal sentience) signed in England in 2012 by 15 leading scientists, and overseen by Stephen Hawking himself.

“The field of Consciousness research is rapidly evolving…and this calls for a periodic reevaluation of previously held preconceptions in this field…Birds appear to offer a striking case of parallel evolution of consciousness. Evidence of near human-like levels of consciousness has been most dramatically observed in African grey parrots. Mammalian and avian emotional networks and cognitive microcircuitries appear to be far more homologous than previously thought. Moreover, certain species of birds have been found to exhibit neural sleep patterns similar to those of mammals, including REM sleep and, as was demonstrated in zebra finches, neurophysiological patterns previously thought to require a mammalian neocortex.”

Superhuman chimps…and crows

A Caledonian crow called Betty demonstrated human-like intelligence a few years ago by making complicated hooked tools from bits of wire to fish items out of tubes. To put this into perspective, it´s something chimpanzees (and most humans) are unable to do.

And like Betty, chimpanzees are also cleverer than us in some areas. In a Japanese study to test short-term memory, numbers were shown on a computer screen before being hidden by white squares. The five-year-old chimpanzees (who were taught to count from 1-9 in advance) beat adult humans hands-down in remembering where each number was hidden. Another study of long-term memory in chimpanzees also gave impressive results, proving the average human is not so special after all.

Apes can also learn and understand sign language, and there is evidence that parrots don´t just repeat words; they also understand meaning. Dogs who wait patiently by the door five minutes before their owners return from work are not only expressing an awareness of time, but evidence of a sixth sense too (as a side note, canines even align themselves to the Earth´s magnetic field when doing their business). Scientists have also recently discovered that not only are dolphins math geniuses,

Teenage dolphins have been filmed ´getting high´ on pufferfish..it´s not big but it is clever

CREDIT: deviantart.net

but that juveniles also like to chew and pass around pufferfish for no other reason than to ´get high´ with their buddies- not dissimilar from rebellious youth behavior in our own species!

Furthermore, magpies, dolphins, great apes and elephants can recognize themselves in a mirror just like us, and many studies show a clear awareness of death in some species. One of the most compelling (and tragic) from Bekoff´s colleague Jane Goodall is detailed here. The behavior of this young chimp who lost his mother and died three days later of a broken heart leaves no room for doubts about his understanding of death.

Depression, grief and mourning affect many animals in exactly the same way as us

Other researchers from Kyoto university witnessed two grieving chimpanzee mothers carrying their dead infants for 68 and 19 days respectively after death, as though they couldn´t bear to say goodbye. To Berkoff, it´s simply “arrogant and wrong” to assume we are the only species in which grief has evolved: the only part we don´t yet know is the why. Elephants are especially known to grieve after the loss of a loved one. They mourn the dead by touching the bones or circling the body. Some researchers have suggested they may even relive memories and understand death in just the same way we do.

Videos of animals exhibiting ´human-like behavior´ have gone viral on YouTube. Among them are a herd of buffaloes who get ´revenge´ on a pride of lions, a heroic dog who risked his life to drag his unconscious companion from the freeway, a baby elephant who cried real tears for five hours after his mother attacked and rejected him, and a cat mourning the loss of a friend.

But skeptics warn against anthropomorphism, the misguided attribution of human-like qualities to animals. They claim we must always look for another, more basic, explanation before claiming other creatures are as complex as us. A skeptic might suggest, for example, that if a rat does not want to hear its companion being tortured, this is simply because the rat is averse to the sound of squealing. Rowlands offers a good debunking of this kind of argument, though. He points out that he, too, is averse to the screams of a tortured man, but it is precisely because he feels empathy that the sound is so unbearable.

“It´s widely accepted that many animals display and feel a wide array of emotions including joy, happiness, pleasure, love, empathy, compassion, sadness and profound grief,” Bekoff states. But, he argues, these are not human expressions at all, they are animal expressions. And the reason we share them with so many other species is because we are animals too, whether we like to admit it or not. “We must never forget that our emotions are the gifts of our ancestors, our animal kin,” Bekoff points out.

Animal rights….or Animal equality?

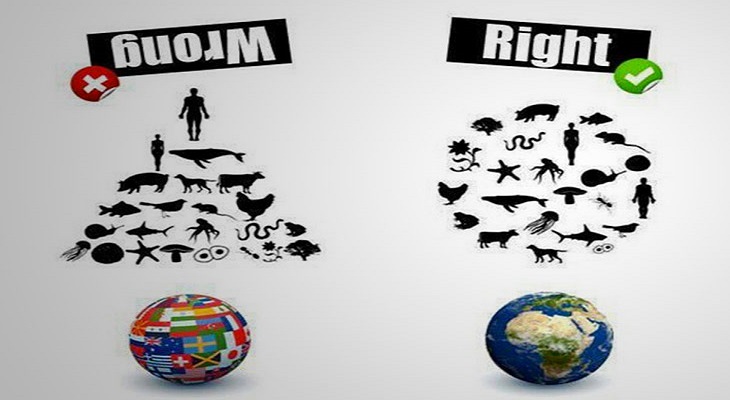

Yet historically, mankind has always treated animals with great disrespect and cruelty, as nothing more than chattel to be exploited for food, work, ´sport´, protection, entertainment and experimentation. Judaism, Christianity and Islam alike all teach that humans were given the right to use (and abuse) God´s lesser creatures, rather than preaching a sense of responsibility and stewardship towards them. The idea that we are not alone in feeling pain, anxiety, shame and depression is therefore highly uncomfortable for humans. If we accept this, how can we continue to treat animals as we do, or go on believing we are superior?

And in any case, some may ask what right we have to superiority? We are the most destructive and violent species on Earth. As animal rights activist Steven Best rightly argues: “We cannot overlook an amazing paradox. It is an odd but revealing phenomenon that a species which so arrogantly prides itself in its alleged unique skills in reason and communication has not yet attained an accurate understanding of itself. This advanced “intelligence” of humans, moreover, is in the advanced stages of exterminating our closest biological relatives, along with millions of other animal and plant species, thereby ensuring that Homo sapiens will die as it was born – in ignorance of its own nature and the other animal species vital for an accurate self-understanding.”

It´s not what we want to hear, but maybe it´s what we need to hear. But where next? Berkoff is more positive. “We need to work for a science of peace and emphasize the positive, pro social side of other animals and ourselves. It’s truly who we and other animals are.

“People who claim nonhuman animals are inherently aggressive and warlike are wrong,” he goes on. “When they use information from animal studies to justify our own cruel, evil behavior, they’re not paying attention to what we really know about the social life of animals. Do animals fight with one another? Yes. Do they routinely engage in cruel, warlike behavior? Not at all. When people say, ýou´re behaving like an animal, it´s actually a compliment.”

Berkoff adds that we also need to “debunk the myth of human exceptionalism once and for all. It’s a hollow, shallow, and self-serving perspective on who we are…of course we are exceptional in various arenas, as are other animals.”

Source: True Activist

Related:

- New Zealand Now Recognizes ALL Animals As Sentient Beings!

- Circus Lion Freed From Cage Feels Earth Beneath His Paws For First Time

- Elephant Cries Tears Of Joy After Being Released From 50 Years Of Captivity

- Disturbing Aerial Photos Show What Killing Billions Of Animals For Meat Is Doing To The Environment

- What if Animals Treated Us How We Treat Them?

- 11 Thought Provoking Images Show What Humans Are Really Doing To The Planet

- You Will Want To Recycle Everything After Seeing These Photos!

- This Film Should Be Seen By The Entire World!

- Seed Bombers Can Plant An Entire Forest of 900,000 Trees A Day!

- Shocking Effects Of Deforestation Exposed In Brutal Print Ads

- Costa Rica Becomes The FIRST Nation To Ban Hunting!

- Ecuador Just Set The World Record For Reforestation!

- Bolivia Gives Legal Rights To The Earth

- This Indian Man Planted an Entire Forest by Hand

- How India is Creating 300,000 Jobs AND Planting 2 Billion More Trees

- Everything Wrong With Humanity, In A Short Animated Film

- These 29 Clever Drawings Will Make You Question Everything Wrong With The World

- The Earth is a Sentient Living Organism

- Earth is Alive! Beautiful... Finite... Hurting... Worth Dying for!

- 4 Minutes That Will Change Your Life

- Possibly the Most Eye Opening 6 Minutes Ever on Film

- Gray whale dies bringing us a message — with stomach full of plastic trash

- Longest Floating Structure In History Sets Out To Clean The Ocean In 2016!

- Floating Seawer Skyscraper Rids The World’s Oceans Of Plastic While Generating Clean Energy

- Paradise or Oblivion (Documentary) - The Venus Project

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete