Though Leonardo da Vinci endures as the quintessential polymath, the epitome of the “Renaissance Man” dabbling in a wide array of disciplines — art, architecture, cartography, mathematics, literature, engineering, anatomy, geology, music, sculpture, botany — his interest in science was anything but cursory. In Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist (public library), Martin Clayton, senior curator of the Royal Collection, looks well beyond his iconic Vitruvian Man to explore Leonardo’s remarkably accurate anatomical illustrations that remained hidden from the world for nearly 400 years after Da Vinci’s death.

How one of history’s greatest artists almost became history’s greatest anatomist.

A study of a man standing facing the spectator, with legs apart and arms stretched down, drawn as an anatomical figure to show the heart, lungs and main arteries.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Three studies, one on a larger scale, of a man’s right arm and shoulder, showing muscles; three studies of a right arm; a diagram to illustrate pronation and supination of the hand.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

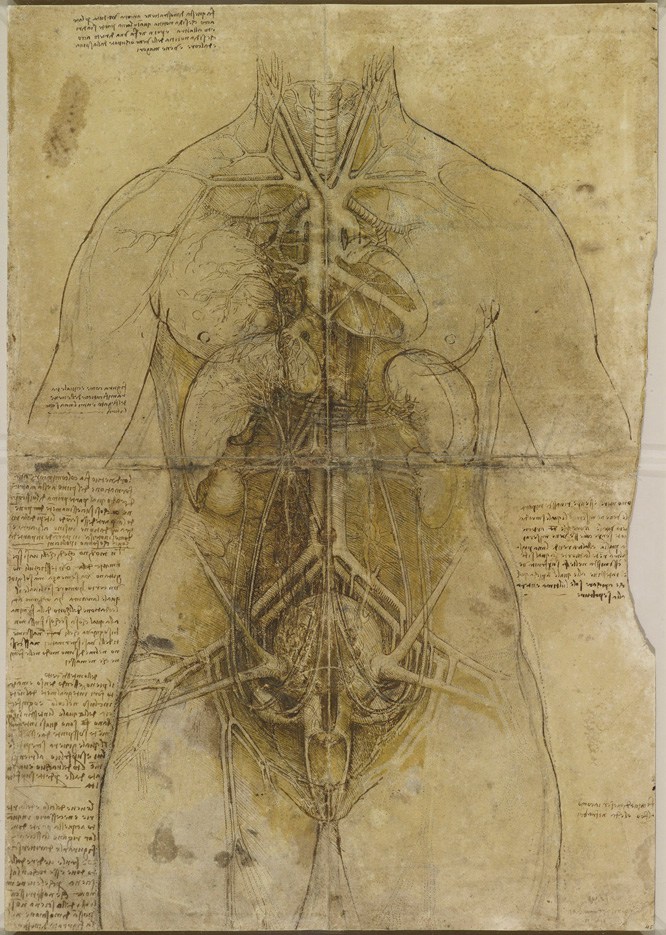

An anatomical study of the principal organs and the arterial system of a female torso, pricked for transfer.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Springing from the “true to nature” ethos of his paintings, Leonardo’s fascination with the human body took him to the morgues and hospitals of Florence, where he performed dissections of corpses, often of executed criminals. His greatest feat was understanding the workings of the heart. After discovering a bulb-shaped swelling at the root of the aorta, he came strikingly close to uncovering the mechanisms of blood circulation more than a century before formal science arrived at it. In fact, he injected melted wax into the heart of an ox, then a glass model of the cast and pumped it with water with a suspension of grass seeds in order to observe the vortexes at work. He then concluded that the swelling made the aortic valve close after each heartbeat, a proposition which cardiologists didn’t arrive at until the early 20th century and didn’t fully confirm until the 1980s.

Large drawing of an embryo within a human uterus with a cow’s placenta; smaller sketch of the same; notes on the subject; illustrative drawings in detail of the placenta and uterus; diagram demonstrating binocular vision; a note on relief in painting and on mechanics.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

A study of a man’s left leg, stretched forward; beside it, a man’s legs seen from behind; below is a man standing, turned in profile to the left, with his left leg advanced; to the right are two studies of the bones of human left legs and thighs, and one of an animal; with many notes on the muscles.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

A study of the dissection of the lower leg and foot of a bear, viewed in profile to the left. To the left there is also a slight drawing of the leg.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Perhaps his most famous anatomical drawing was of a 100-year-old man, who had reported being in excellent health mere hours before his death. When Leonardo dissected him to see “the cause of so sweet a death” and found cirrhosis of the liver and a blockage of an artery to the heart, producing the first-ever description of what is now known as coronary vascular occlusion.

As a great artist, Leonardo had two advantages over his contemporary anatomists. First of all, as a sculptor, engineer, architect, he had an intuitive understanding of form — when he dissected a body, he could understand in a very fluid way how the different parts of the body fit together, worked together. And then, having made that understanding, as a supreme draftsman, he was able to record his observations and discoveries in drawings of such lucidity, he’s able to get across the form, the structure to the viewer in a way which had never been done before and, in many cases, has never been surpassed since.

Drawing of external genitalia and vagina, with notes; notes on the anal sphincter and diagrams of suggested arrangement of its fibers and its mode of action.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Five studies of the bones of the leg and foot; a drawing of the knee joint and patella; two studies of the bones of a right leg with the knee flexed; the muscles of a right buttock, thigh and calf.

Royal Collection © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Leonardo intended to publish his drawings as an illustrated treatise on human anatomy, but when he died in 1519, his anatomical papers were buried amongst his private possessions and vanished from public sight. In the early 1600s, around 600 of his surviving drawings were bound in a single collection and by the end of the century, they mysteriously made their way to the Royal Collection. Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist gathers 90 of these seminal drawings, contextualized in a discussion of their anatomical significance. Accompanying the books is an iPad app, presenting 268 pages of Leonardo’s notebooks in magnificent high resolution.

Source: Brain Pickings

Related:

Wonderful blog. See also those mspy reviews.

ReplyDelete