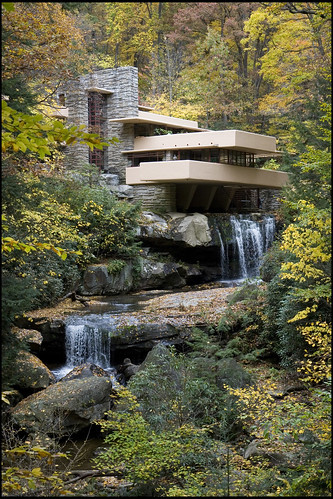

Carol M. Highsmith via Wikimedia Commons Public Domain

Frank Lloyd Wright is regarded as one among American architecture’s most influential personalities. During his decades-long career as an architect as well as an interior designer, he perfected a prolific number of designs, with the iconic Fallingwater at the forefront.

Wright described the 1930s home as “one of the great blessings to be experienced here on earth.” Inspired by Wright's desire to integrate human-made structures into the natural world, Fallingwater typifies organic architecture. As the architect's signature style, understanding the philosophy behind organic architecture is key to grasping the significance of the famous Fallingwater house.

Wright coined the concept of “organic architecture” in the early 20th century. Rooted in his love of nature, the primary intention of organic architecture is to unify buildings with their environments and blur the line between built structures and natural habitats.

This philosophy guided the ins-and-outs of Wright’s whole creative process. Approaching each of his designs as a microcosm of the universe, the architect sought uniformity through repeating patterns. He also paid close attention to the setting of each structure, culminating in incredibly site-specific—and therefore fully integrated—designs like Fallingwater.

In 1935, Wright was commissioned by the Kaufmanns, a prominent Pennsylvanian family, to replace their deteriorating summer house. Nestled along a stream in Bear Run, an Appalachian reserve, this property was an ideal fit for Wright, whose nature-inspired approach had attracted Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann.

Wright reportedly designed the home in a single morning in 1935. When designing the unique abode, Wright made a surprising decision: to build the house above the property’s naturally-occurring waterfall.

Regarded by the Kaufmanns as the centerpiece of the estate, they had hoped to have a view of the cascade. However, they trusted Wright, who reassured them with a philosophical promise.

These thoughtful aesthetic decisions essentially camouflage the dwelling. With its stacked silhouette, stone exterior, and neutral color scheme, it both recedes into its wooded surroundings and accentuates its waterfall. After all, as Wright claimed, “a building should grace its environment rather than disgrace it.”

Wright also designed Fallingwater’s interior with nature in mind. At the center of the home is a sandstone fireplace built around two unmoved boulders. All accents are painted Cherokee red, a burnt crimson color reminiscent of lumber. Similarly, the floors are stone, and the walls are covered in unwaxed cork. Large, corner-less windows welcome “the natural environment into the house as well as enticing its inhabitants out.”

This idea of bringing the outdoors inside is also evident in the home’s collection of freestanding and built-in furniture. Fallingwater houses 170 decorative art pieces designed by Wright that channel the outdoors through both look and feel. Many of these furnishings are made of North Carolina black walnut, a wood with warm chocolate tones, and veneered in sapwood.

Finally, the house grants easy access to the outdoors in creative ways, including a staircase that takes visitors from the living room directly to the stream!

According to Mymodernmet, The Kaufmanns owned Fallingwater until 1963 when Edgar Kaufmann, Jr. donated the house and its 1,500 surrounding acres to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. “It has served well as a house, yet has always been more than that, a work of art beyond any ordinary measure of excellence,” he said. “Itself an ever-flowing source of exhilaration, it is set on the waterfall of Bear Run, spouting nature’s endless energy and grace. House and site together form the very image of man’s desire to be at one with nature, equal and wedded to nature.”

Now a museum, the site welcomes eager architectural fans from all over the world. Featuring a range of tours tailored to visitors’ interests, exploring Fallingwater firsthand is an ideal way to appreciate this great blessing.

COMMENTS