Not only can unhatched bird embryos hear the warning calls of adult birds, but they can also communicate that information to their unhatched brothers and sisters sharing the same nest, remaining safely tucked away in their shells until it's safe to hatch.

It's a finding that reveals how birds can adapt to their environment even before birth, as, unlike placental mammals, their physiology can no longer be influenced by changes in their mom's body after the egg is laid.

A team of researchers has particularly exposed unhatched yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) eggs to cues that indicated high predation risk. Not only did the unhatched embryos communicate those cues to unexposed nestmates, but they also emerged from their eggs exhibiting much more cautious behavior than the control group.

In fact, the experiment itself is pretty elegant. The team collected wild gull eggs from a breeding colony on Sálvora Island in Spain which experiences fluctuating levels of predation, particularly from small carnivores such as minks.

Noguera & Velando, Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2019

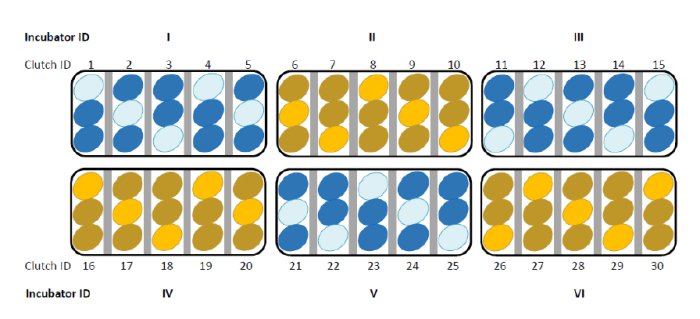

Those eggs were divided into clutches of three eggs and placed in incubators. Then they were assigned to one of two groups - the experimental group (yellow in the picture), or the control group (blue).

From each clutch, two of the three eggs were removed four times a day from their incubator handled, and put in a soundproof box where they were played recordings of adult predator alarm calls.

For the control group eggs, no sound was played inside the soundproof box.

They were then put back in the incubator, in physical contact with the 'naive eggs' which had remained behind.

The eggs which had been exposed to alarm calls tended to vibrate more in the incubator than the eggs that had been placed in the silent box.

The experimental clutches, including the naive eggs that hadn't been exposed to the alarm calls, took longer to hatch than the control clutches. When they emerged, all three chicks in the experimental clutches showed the same developmental changes.

Compared to the control chicks, the experimental chicks made less noise, and crouched down more - a defensive behavior usually made in response to adult alarm cries.

All three chicks in each experimental clutch had physiological characteristics not seen in the control clutches. They had higher levels of stress hormones, fewer copies of mitochondrial DNA per cell, and a shorter tarsus, or leg.

According to statistical analyses, these physiological differences cannot be attributed to incubation length alone. Since the only difference in the treatment of the clutches was the alarm calls, and as the only observed difference in the behavior of the eggs was the vibration rate, it looks likely that unhatched chicks can communicate danger to their nestmates via vibration.

This research has been published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

COMMENTS